Apple's decade-long software katabasis (1989-1999)

As far as real-life, modern-era katabasis stories go, there is perhaps none more so ubiquitous to the legacy of Apple Computer than its (in)famous “turnaround” at the hand of Steve Jobs after the purchase of NeXT in 1997. From a software developer’s standpoint, however, the “smooth transition” to Mac OS X was nothing short of a long time coming, with two intermittent releases that acted as life support to an increasingly dated Mac OS nanokernel, having existed from the first Power Macintosh models of March 1994 up until the final release of OS 9 around the turn of the new millennium. This might not seem like a great deal of time passed, but the absolutely staggering progression of software technology through the course of the 90’s contributed greatly to Apple almost being left in the dust by the time that Windows 98 came rolling around. To quote Norm Macdonald’s post-SNL monologue, Steve Jobs went from not being important enough “to even be allowed in the building” to, 11 years later, being important enough so as to land an interim CEO position in a last-ditch effort by Apple’s Board of Directors to breathe ‘new life’ into the company. What then happened was not a massive turnaround effort on behalf of Jobs, but instead a gradual decline exhibited within Apple, as evidenced by a shift in its corporate philosophy. Steve would oversee a transition between operating systems that would not go without disgruntling many a developer for the platform, but eventually landed the Macintosh in a more favorable position with consumers.

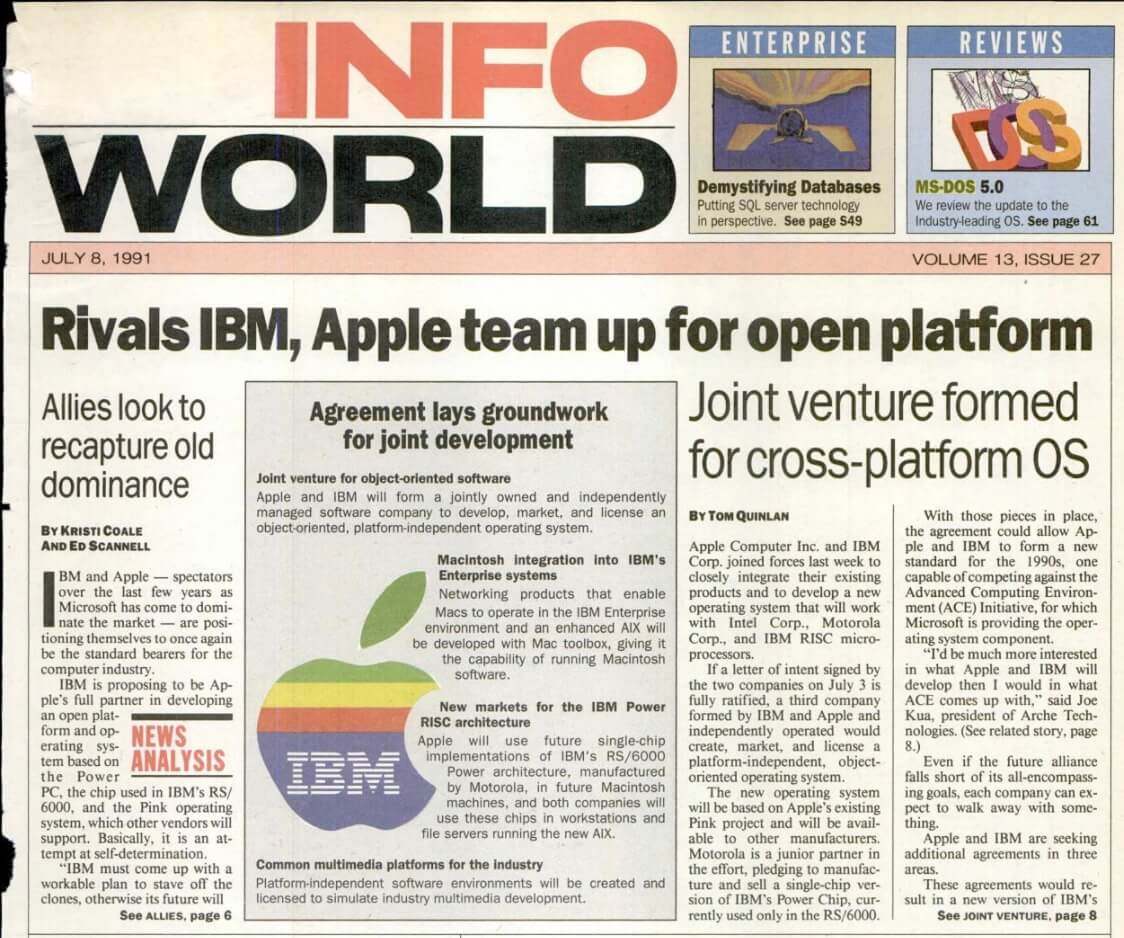

Before the much-belated Longhorn, there was Copland. By the time that System 7 of Mac OS had been released on 13 May 1991, the technical management team at Apple had already been planning for a subsequent release, known to Apple’s developers as ‘the Pink team,’ as opposed to the ‘Blue team’ working on the latest and foremost iteration of the system. What then became known as Project Taligent was a cross-company effort between Apple and IBM to develop a memory-protected, object-oriented environment to the likes of NeXTSTEP, the UNIX-based brainchild of Steve Jobs’ NeXT Computer. The Apple/IBM partnership was incorporated in 1992, to where just 8 years earlier, a partnership between “Big Blue” and a Jobs-driven Apple Computer would have seemed entirely unfeasible. However, the Apple of the early 90’s was heavily driven towards cross-company alliances, such as the PowerPC “AIM” alliance between Apple, IBM and Motorola that gave us the PowerPC architecture of chips predominantly used in the Macintosh for just over a decade, well into Jobs’ re-acquisition of Apple and later transition to Intel x86 in 2006. As such, under the leadership of John Sculley, Apple was heavily drawn into joint projects between companies that would have otherwise seemed treasonous to the likes of Jobs. The company thus suffered a crisis of identity when Sculley took to calling Apple a “software company” and, by 1995, facilitated the licensing of Mac OS to third-party manufacturers on a per-computer royalty basis. In essence, what had previously been the tight coupling between hardware and software had instead turned into the general development of software for a wide variety of PowerPC-based clone computers, with a secondary focus on producing real, Apple-manufactured computers.

While the AIM alliance was an unbridled success in producing an architecture that propelled Apple for the next decade, the Taligant effort was plagued from the start with intra-company struggles between competitive development staffs that prohibited the realization of a unified goal for the project. By 1994, the project had gone for two years without producing anything substantial until Hewlett Parckard briefly joined the partnership, shortly followed by its withdrawal in tandum with Apple itself, leaving IBM with the shit end of the stick. Perhaps the most inventive thing to come out of this collaborative alliance was the CommonPoint application framework, launched in 1995, as part of which was then spurned into the Java Development Kit just two years later. (Or, if you are a Java programmer, this might instead be the most irritating thing—take it or leave it!) It was around this time that Apple made a last-ditch attempt to supplant the rapidly-aging System 7.5 (codename “Mozart”) with the partial implementation of a new kernel under System 8 (codename “Copland”). Work on Copland began in 1994, though, much like the now-famed Longhorn disaster, the effects of “feature creep” began to shovel more expectations upon an ever-increasing package size. With the inclusion of more half-witted features came severe detriment to the operating system’s degree of stability, and, by the time of August 1996, the first Developer Release was panned for being completely unusable for development purposes.

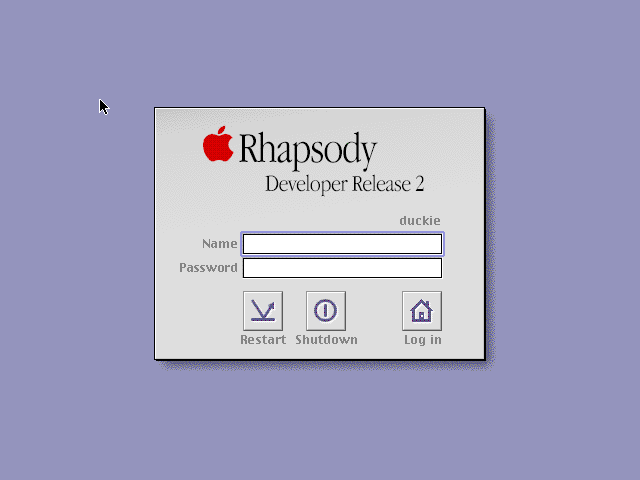

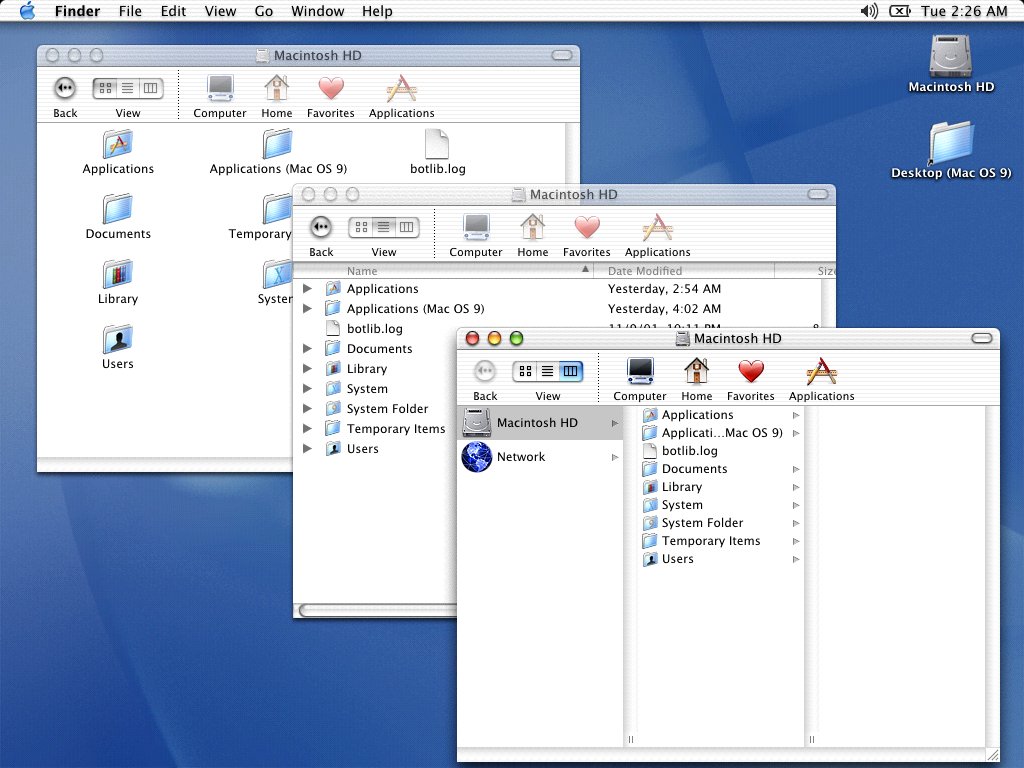

This rather hopeless situation was one of the many factors that contributed to Apple’s December 1996 decision to merge with NeXT and bring Steve Jobs on-board with it. Many of Apple’s developer circles were under the belief that the company would instead adopt Jean-Louis Gassée’s BeOS, which I have previously quipped about in discussing the Be-clone Haiku. In fact, BeOS was severely underqualified in the wake of NeXTSTEP, especially with regard to end-user security. And so, the NeXT port to Macintosh became “Rhapsody,” which eventually became Mac OS X. In the meantime, System 8 was revised to include some of the features expected for Copland and, along with OS 9, began to take on the role of a stop-gap until the OS X Developer Preview was officially announced on 11 May 1998 and released just under a year later. Along with simplifying the hardware product line, one of Jobs’ key focuses as interim CEO was realigning Apple’s technical management towards that “tight coupling between hardware and software” which had once aptly described the company. In doing so, Jobs put an end to the practice of licensing software to clone manufacturers with the release of Mac OS 8, with few exceptions. The newfound primacy given to software thus elevated the importance of the Macintosh operating system as a source of attraction for new consumers of the Apple ecosystem, rather than the ball-and-chain that was Copland. That being said, however, Copland did eventually fulfill its intended goal as a stop-gap between the existing System 7 kernel and the UNIX-based NeXTSTEP derivative that would come to be known as Darwin (which continues to power macOS to this day).

Jobs, by his own admission, was not on the cusp of the development-level changes being made to Apple’s software lineup. Instead, his greatest strength was in surrounding himself with the right people. Throughout his time both at Apple and NeXT, Steve exhibited a hands-on approach when it came to plucking talent and, most infamously, discarding of it. All of this brings me to shining the spotlight on Scott Forstall, who became part of NeXT in 1992. Over the course of the company’s development up until its ‘97 merger with Apple, Forstall began to take on the role of software development, with a particular regard for user interface design. Forstall was a leading designer of the fluid-like Aqua user interface that shipped with Mac OS X in 2001. The design language of the post-Copland Macintosh operating system and, subsequently, the iOS mobile operating system, were dominated by Forstall’s creative influence and an all-pervading design philosophy that has since become widely known as “skeuomorphism.” However, internal divisions within Apple between the hardware and software design teams would eventually culminate in a 180-degree turnaround with the radically different design language of iOS 7, followed by OS X Yosemite. I intend to further discuss this trend in my next blog post, which shall account for what I perceive to be a steady decline in both the form and function of Apple’s software, beginning with the corporate decision to fire Forstall from the company in October 2012.