Why is it so important to 'think' like a historian?

In my defense of this incoming, most lengthy diatribe over seemingly nothing: this was all spurned by what was originally an attempt to explain, in short, why students should regard the discipline of History as something greater than an exercise in rattling off various dates and terminologies within the grand historical consensus. The very cynical proposition of a “grand historical consensus” on my part should indicate towards my personal disposition with regards to the almost oxymoronic nature of ‘objective histories.’ To say the least, the Greek verb história (commonly translated as “learning through inquiry”) does not necessarily pertain to ‘history’ as a structured academic discipline. This is not to say, however, that we might infer the ‘true’ (or shall I say ‘sense-perceived’?) nature of such an important discipline using only its ancient root. (Throughout this post, you will find us using the ‘royal we,’ but in rare instances, I will be using the ‘patronizing we.’ There will be no further clarification upon which one is being used.)

And yet, etymologies remain as telling as ever. História, stemming from the verb historéō (“to inquire”) takes from the root hístōr, which is simply a noun that, in the third declension, can either refer to a ‘judge’ or ‘witness.’ It just so happens that a historian, in this context, must carefully balance between both these roles in order to impart upon the reader something that amounts to more than mere tellings of still life. Though ‘still,’ past lives contain an inertia which lend to driving civilizations towards their ultimate state: whether it be a dialectic conflict of thesis and antithesis ending in its resolution, as described by Hegel, or what Fukuyama infamously pronounced “the End of History…” maybe even seasoned with a rather German touch of Spengler, portraying the cyclical “beginning and end” of civilization not unlike that of a biological organism. However though you might be inclined to have your particular flavor of historical theory, it alas remains impossible to make clean break between an inquiror and his subject of inquiry, for the very subject itself being inquired is done so at the behest of its ‘witness.’

We should now be well aware of the fact that the ‘wits’ of even the most well-balanced of witnesses prohibits there from being any ‘objective history.’ This is all to say that histories are often juxtaposted with myths, which are often portrayed with much greater plasticity than the likes of Xenophon (“xeno,” in this context, meaning “strange,” coupled with the ‘sound’ of “phonos,” to make “strange voice”) who is criticized for infringing upon philosophical, perhaps even Socratic forms of thinking in his Cryopaedia of Cyrus the Great. Herodotus, on the other hand, gives casual mention to giant Myrmekes indikoi (“Indian ants”) whose gold-digging prowices explain the source of Persia’s wealth, originating from the part of ‘Northern India’ (perhaps now better regarded as stretching from the Syr Darya into modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, but no further occidental than Tehran) which Alexander would later conquer using the name ‘Bactria’ (circling back to the Achaemenids). In spite of the plasticity of these histories, they are both integral to our understanding of the Greco-Persian Wars, and while it is true that they are mythically disposed, they are done so in just the same fashion as some myths themselves. This does not, in my opinion, at all substract from their mammoth stature among the classical corpora.

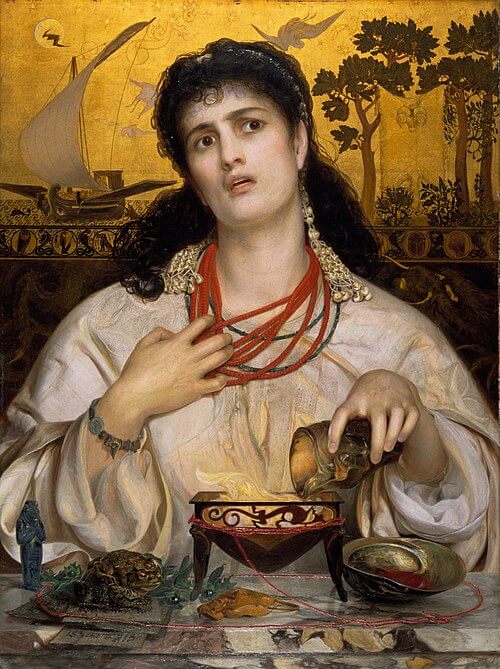

One of the first things that was drilled into my head as a student of mythology is that myths are not to be regarded as none more important than “things that didn’t actually happen.” To the contrary, it has become rather commonplace for serious philologists to acknowledge the influence exerted by oral tradition upon the magicks, or maleficarum, of characters such as Circe. (In fact, the mythic behavior of women in the myths is a whole topic in and of itself, but there is no doubt in my mind that Circe, if she were keen on the ‘cancel culture’ movement, would take up in her misandry alongside Medea.) To avoid dipping into the contextless: Medea was a beautiful pharmakeía (“sorcress”) who, after ten years, was ‘left out to dry’ by Jason, for which she robbed him of any legacy by, well, killing the new girl, along with both their children. (Bring me Apollonian misogyny, and I raise you the feminine physis of misandry! Don’t you just love antitheses?) I hope this expedition of psychological tropes within mythoi (pl, mythos) should demonstrate that, far from but sweet nothings, they speak less upon most temporal, literal affairs in lieu of this most complex abstraction of the human condition.

"There is no homecoming for the man that draws near them unawares and hears the Sirens' voices." (Odyssey XII)

"...and with all the sweet kisses of addiction, it's calling me to break my bonds again!" (Hammill)

In much a similar manner to how Odysseus is drawn into “the Siren Song” in which they sing about the history of the world, with a maddening allure of forbidden knowledge regarding the Trojan War; the very concept of a ‘world history’ is an alluring, though deceptive front for a gargantuan set of narratives presented so as to follow one after the next, but only if the stars align precisely. What have become of the thick paperweights that once adorned primary school bookshelves, rarely pulled by students (but in daring vandalisms) and often returned with haste upon eliciting greater confusion? As a part-time substitute teacher in the modern era, I can only state to reason that they have been replaced with cheap notebooks; their pages, made Acrobatic… their reading, more cumbersome than before. (Your privacy, never there to begin with.) I am left tempted to feel as if the Illiad and Odyssey might have served better as educational texts than our own Pearson myths. Furthermore, said narratives come to even greater fruition when you are inevitably short-stomped by the apparently unbounded terror of the Enlightenment, and there is no hope to be had from reading thereon. In doing so, you would be better off stepping into the Library of Congress and sourcing the narrative from its direct purveyor of historical farces—straight from the horse’s mouth. Indeed, history textbooks spare no place for graphics and find all sorts of ways to decrease the amount of black ink that bleed betwixt, for it has now all become part of appealing to the younger generation so that they might, in their favorance for pictorial stimulus, perhaps do away entirely with the lexical. (Addendum: it must also be acknowledged that both lexical and pictorial stimuli are crucial in terms of the cognitive processing of both visual and conceptual forms of comparison; we are not trying to paint a false dichotomy.)

Can’t you see, there is no such thing as overdosing on hyperbole. It is also an attempt on my part to ‘future-proof’ this article so that Google might decide to plant my all-pervasive historicism into the minds of unsuspecting iPad kids. And so, this brings us to the matter of historicism. It was not that long ago going into the previous century that Historicism was frowned upon by many a History department head, since then becoming the de-facto standard for historical criticism. Having followed the rise of such a controversial “discipline” as Sociology, it has since come to place great emphasis on the importance of understanding the respective historical contexts in which any given period of literature might have lent to its interpretation among contemporary readers. In essence, it may be characterized by the need to encapsulate the ‘moment’ of the history therein; and, to historicists, this is more elementary to understanding the nature of the text than, per se, an exercise in synthesis with the ‘timeless’ aspects of man, otherwise dealt with by myths. This inevitably descends into the moral relativism of cultures and their changing attitudes towards the most ‘determined’ of human ethics (in essence, disregarding the sentiments of moral rights and wrongs and supplanting them instead with a more normative moral attitude).

With the so-called ‘New Historicism’ entering the academic vernacular, any hopes of recovering from relativism and all its faucets must surely have escaped whatever few “anti-historicists” remain left amongst the faculties. Okay, so let us for now disregard Schlegel, and any other German to speak of, so that we might rest our sights upon what it truly means to think like a historian. (For now, German historians need not apply.) I am generally confident that memorizing dates and preconcieved eras is none short of folly in the equal absence of some understanding as to why history tells it the way it is. If you are simply reciting numbers all the while trying your best to recite a direct quote from another historian, what’s the purpose? If you’re just echoing the mental entrails of dusty, dead men—life no longer has any meaning, except as a discordant source of hoarse dissonance, be it cognitive or whatever have you.

Anyone can be a historian!

What if I told you that a ‘historian’ doesn’t have to know about everything that ever occurred in history, or that ‘histories’ are more than just pseudo-objective, dime-store chronologies of past happenings. Perhaps that is sufficient to meet the mental rigors of most high school level history courses, but I, for one, was only set aback upon learning what historical scholarship generally consists of, not just among paper-pushing word count-maxxing (what we might call a “skill issue”) students, but also the self-identified ‘scholars’ themselves. It is from this experience that I can state on good authority that being a ‘historian’ is more demanding of an open attitude towards the synthesis/analysis of various, invariably contradictory historical accounts. By adopting this attitude, an academic is given ample coping space to grapple with the sheer unknown while also engaging with it in familiar ways, and, if you learn how to appreciate this attitude, you may do well in using it.

Fun fact: the human brain cell and muscle cell both originate from the same master of embryonic stem cells. Our ever-growing confusion about the age-related loss of neurons has (understandably) turned over some controversy about the exact nature of “adult brain cell death,” but, this is to say: you had better use it or lose it! If you neglect the tasks of reading and memorizing, prepare to someday find yourself drained of all capacity for them, and left to rot away in the fleshly corpse of ‘past knowledge.’ (It’s all past knowledge…) Seriously, though: in doing this, you are actively consigning yourself to everlasting foolishness. My most severe form of dread is reserved for scholars whose existing knowledge prohibits, rather than encourages, the continued pursuit of greater knowledge. The constant acknowledgement of one’s own scholarly limitations does indeed make season their personality into more than that of a Talking Head, “letting the days go by.” So, believe me when I say, the only thing I know is that I know nothing.

Alas, if you want to be the kind of scholar whose high horse knows to get below you, maybe then consider the “Petersonian Method,” an abridged, reversed form of the Socratic method that I have generously named after Dr. Peterson. In this particular context, it is being used to loosely satisfy what might otherwise be perceived as direct questions. Using this method, however, there is no such thing as a ‘direct question,’ almost as if you have been swallowed up by Peterson’s “belly of the beast” of incoherent thoughts. (It can alternatively be described as a treatise of dishonesty.) Let me just say that, for the record, I am not a ‘hater’ of Dr. Peterson in spite of his (sometimes) rather questionable academic output: it just so happens that he loves to split hairs with semantics, almost seemingly more so than actually holding any form of debate. He takes to this behavior almost as much as his love of staving off those student heathens from his most invaluable lectures. Nevermind… perhaps those lectures raise more questions than the Doctor could ever hope to answer. Oh well—in spite of Dr. Peterson being a “practicing clinical psychologist” as he so loves to remind everybody in each of his public outings, he is also a shining example of this particular manner of thumb-twiddling. “Well, first, what exactly do you mean by thumb-twiddling?”

The “Petersonian Method” of Reasoning

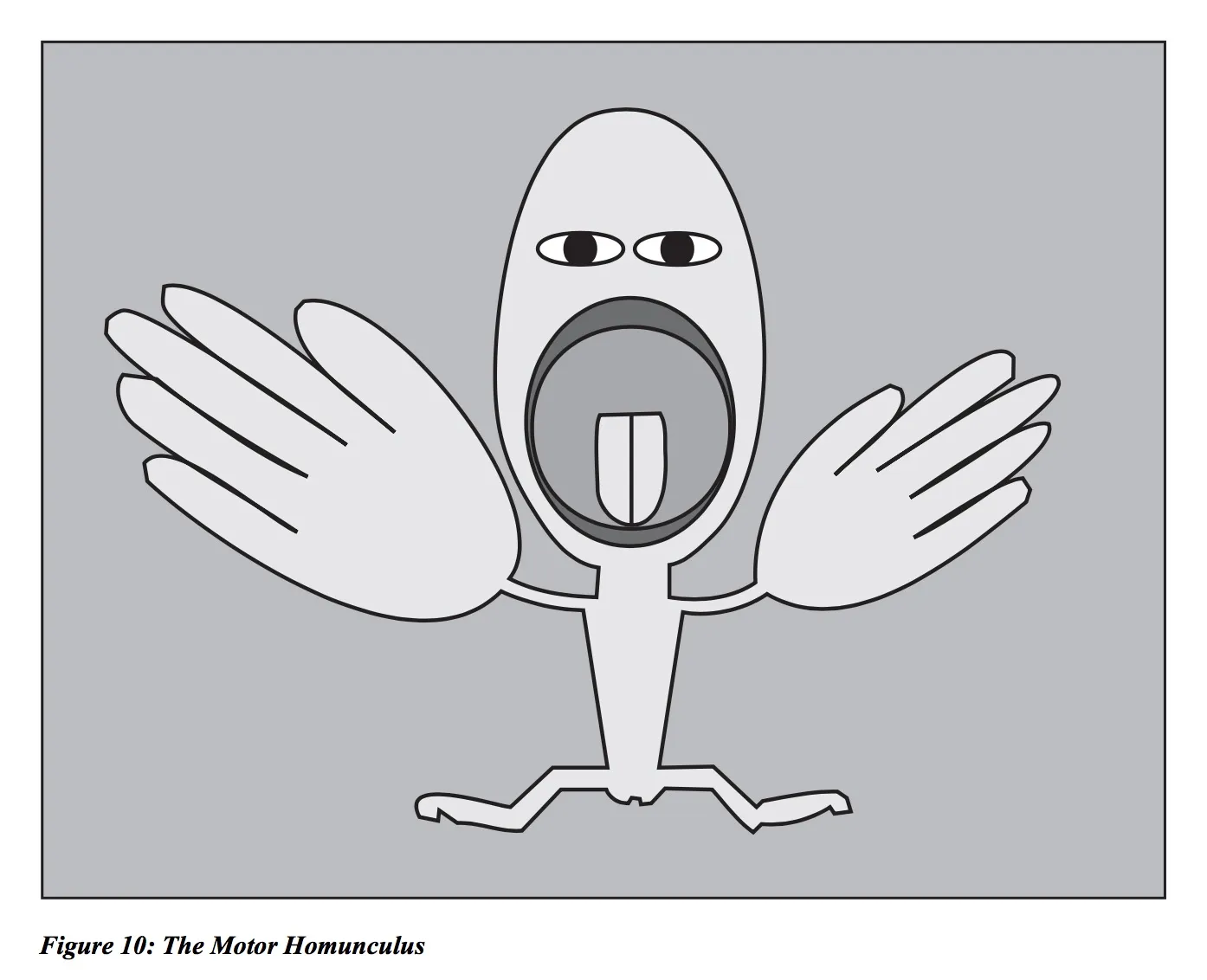

This is our very own Motor Homunculus, so say hello. He goes, "I'm taking the descent into my disintegration, sitting among all this anomalous information!" (para. Peterson fig 4, musical adaptation of Maps of Meaning)

Now, consider the following exercise: what do you think happened during the Fall of Rome? (If you answered with “Rome fell,” then I fear you might be the lifelong student of Grammarly, for whom shifting around words is supposed to leave things displaced ‘out-of-the-box.’) Instead, if you are asked, “Why might the Fall of Rome be important to European history as a whole,” perhaps consider that the very structure of such a question indicates that it is, at the least, important, for it is, after all, one of the most romanticized events of the Renaissance period. You need not know this, though, to proceed with formulating your own argument. It is “important to European history” in the least because Rome was a very important city, and so its very ‘falling’ should indicate that, “The supposed downfall of the city probably had numerous effects on the balance of powers in Europe.” This is a perfectly generic, most untantalizing thesis, but it is, alas, a thesis, albeit an easily defensible one. The only necessary logical conclusion in order to prove such a claim is by expounding upon what makes “the balance of powers” definitionally ‘important,’ at which point whole the thing now borders upon being overly self-evident.

If you are asked, “What happened in 476,” to which you reply with, “I don’t know,” you are not thinking like a historian, or at the very least, an academic. Academics take to forms of rhetoric like flies to shit, all the while excreting new devices in the process. Instead, consider saying, “Late Antiquity as a whole marked a huge turning point in Europe, and the start of what historians consider the Medieval period.” In essence, this broadly accounts for “what happened” without acknowledging the relevance of the year 476 to either the Late Antiquity nor Medieval periods. Such a response might bring one to suspect that our historian does not know the relevance of the year itself, but associates the “Fall of Rome” with a broadly contextualized European setting.

Suddenly, you can ‘answer’ pretty much any question with varying degrees of historical detail by using what relevant information you do know and positioning it aggressively. YouTube historians love to do this, to where each and every subject of discussion will simply degenerate into the same hundred year historical outline. Of course, historians are not the only academics guilty of overspecialization; it’s just simply too easy in our webby age to avoid being tempted by taking the reigns as the hopeful ipse dixit on one or two particular events within history, than to risk being challenged on something pertaining more to the general interest. By constantly levergaging existant knowledge, you avoid being perceived as completely unaware of its greater historical context. And yet, the aforementioned response-claim is certainly more impressive of an answer than, “I don’t know the significance of that date,” just enough so to where the response lies perfectly between Surmise & Conjecture St.

A historian should at least be unafraid to answer a question with another question that begs for more context. I might ask, “By year 476, are you referring to Western Europe in particular?” In doing this, I am making a genuine plead for more specificity which might further inform me to state, “Perhaps then you are referring to the Fall of Rome.” Leaning further towards some degree of academic intrigue, “Rome had a rise and fall, as have most civilizations throughout history, and this seems to be reflective of a greater trend in the progression of civilizations over the course of time.” With this, I am bounding my own historical claim off the question whilst reeling it back into a more generalized historical knowledge. It is by no means a comprehensive answer, but it’s always going to sound better than, “I don’t know.” It is much more of the answer a historian would be inclined to give in the face of such a question. (However, if you are bantering about history, consider avoiding principatatum Occidentis if the date 476 does not at least make itself familiar to you.)

In which case you might be totally unaware of the historical premise, devoid of contextual lifelines, by being asked “When did the Trans-Atlantic slave route take place?” Instead of throwing an “idk,” consider trying to paddle your way further inward by asking, “What do you mean by the term ‘slave route’?” Let us say that if it were then explained, “the slave route is in reference to the use of slave ships for trading slaves,” you might then surmise using existant knowledge that this is probably of some relation to the New World, “It was during the Early Colonial period, traveling from between Africa and the New World.” This would be a rather on-point answer, and achieved with backfiring only one question. It is, nonetheless, a well-positioned question with just enough historical scope (by asking about the ships) which succeeds in landing the correct historical context.

Being a little more cordial

As I hope you might now understand, it is often easy to avoid brain-stumping questions by making resource of more generalized historical knowledge so as to hint towards a more specific occurrence. By doing this, you are at least engaging with the vernacular rigors of the subject like a historian otherwise would, but in much more similar form to that of Jordan B. Peterson. You could perhaps forego the aire of all-knowingness by ocassionally submitting yourself to defeat in saying, “I do not know the answer to what you are asking.” A historian should nevertheless make some effort to arrive at the answer on his own; for, an educated guess, if not always well-enough educated, is always preferable to no answer at all, in this particular context. Perhaps this is not so in other contexts, such as being interrogated before the police, in which you should not go out on a limb with theories, lest you make a Freudian slip.

Why do I think this to be the case? Well, an educated guess is more inclined to engage with what you do know about the material. This promotes increased brain activity and a greater degree of chance that you might remember the direct answer from within the annals of your own mind. If not for this, you are still at least more likely to remember what you now know to be the correct answer, if you are corrected such, because of the mental steps which got you there, and the dialectic exchange an instrument of your mind’s arrival. Ultimately, making mistakes and learning from them is an honorable thing, far more so than snaking your way around and about with semantics in order to trick somebody into believing that you know what you’re talking about. The worst thing that can happen is the potentiality for losing an argument by sinking deep into an indefensible claim, or by failing to defend an otherwise defensible claim, and, in doing so, potentially accruing some respect before the presiding teacher. As it turns out, most teachers in general are delighted to see one of their students taking what they have already learned and carefully applying it to (otherwise unlearned) material. History teachers, I can surely tell you, are delighted at a student’s wholehearted attempt to bring an answer before his fellows. This is indicatory of beginning to think like a historian: by navigating through contextual clues and nuance, and arriving at their own sense of understanding. A lot of debate topics regarding the subject of history, sometimes unintentionally, might stem from questionable dichotomies being propositioned as “this or that,” or “what if that were instead this.” One should always give decent thought to how “this” and “that” are perhaps not always mutually exclusive.

For instance, the “Fall of Rome in 476” narrative itself depends upon the notion that, after Odoacer had deposed Romulus Augustulus (a child emperor noted by his curious anthroponym) the city of Rome was ransacked and had thus ‘fallen.’ In reality, though, Odoacer considered himself no less the rightful Augustus than those who had treaded before the pomerium (the ‘old walls’ of the city) with no less grandeur than he. History is, in fact, rarely a black-and-white matter of business; it often tends to instead deal in shades of grey. Furthermore, historical narratives are just that, narratives, and by implying that the city had ‘fallen,’ rather than simply being characterized as brought under the control of the Odoacer, “the Barbarian King,” the narrative hints towards some contempt for the Goths. (Odoacer was, in fact, an experienced Roman soldier.) More often than not, the fall of one empire precipitates the rise of another, and yet, the “Fall of Rome” is not at all the same as that of the salt-ridden Carthage, or even the lost city of Troy. Rome was a unique city with its own particulars, which is meritous in considering the nature of its ‘fall.’ Some historians posit their own date for the city’s downfall, but in the end, they all rest upon the central impression that Rome did, in fact, come to fall. Part of being a historian is recognizing the implicitness which such a perspective might have served the rest of Europe in portraying the Ostrogoths as bringing about the downfall of such an important, once-triumphant city. For instance, the fall of Rome was indeed capitalized heavily upon by the Eastern Roman Empire (semantics aside, the “Byzantines”) in order to portray their brand of “Roman” as more true to form.

The narrative is further told through the lens of Odoacer’s short reign over Italy and subsequent assassination by Theoderic “the Great.” In fact, both rulers had the support of the Senate of Rome, the latter of whom having worn the imperial regalia in the same manner as the Roman emperors before him. A historian should thus consider how such a narrative has been influenced by the prevailing balance of powers, in light of the city itself having been sacked. After all, Rome was “sacked” a grand total of eight times, and yet, the city still exists to this day. As for the Western Roman Empire, its hands had long slipped from the corridors of power in the periods leading up to the sacking of its capital city. So, Rome had been in a state of decline, but in what manner were the Ostrogoths functionally any different from the Theodosians, or even the Julio-Claudians, in spite their Gothiness? It had very little to do with the new fashion sense parading the Imperial court, nor did anything about fishnets seem anti-Roman (gypsies or otherwise). With this (rather non-invasive) decoupling of the various sub-narratives lying beneath such a matter as deceivingly cut-and-dry as the Fall of Rome, we are left with a rather substantial thesis statement in order to decry the popular historical narrative regarding the mors Roma (“death of Rome”). (This particular criticism of Late Antiquity narrative is not at all untouched by academic discourse on the subject, which is why I have chosen to use it within this article.) Something such as this, in my eyes, is the essence of what it means to ‘think like a historian.’

P.S: I’m still figuring out when to be using “these” and not ‘these,’ but my own personal rules changed somewhat throughout my typing this. (If you read my about page, it says then and there that I am “self-uncertain and ill-informed,” so there it is.) This (rather long) thing has been thrown into the blog because I still can’t seem to figure out if all of my words are playing along to convey something, or if we’re just playing another game of tables and chairs. In all honesty, I once again forwent sleeping all night in favor of one of my writing binges, and it is with no ‘self-uncertainty’ that I say this will not be the last time I decide upon something dumb. My next post will probably serve more personal to me; but, to you, it will just be gibberish, I hope.